Medieval Servant Boy Line Drawing

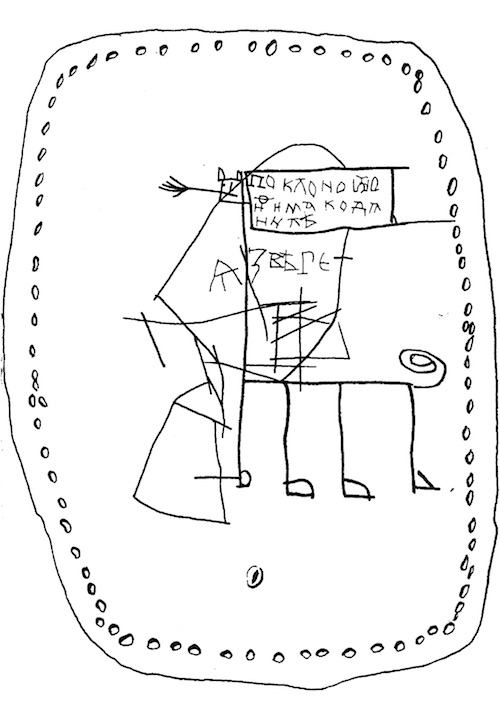

It was not until the fortuitous discovery, well into the Soviet era, of troves of manuscripts in Novgorod that the modern world learned of medieval Slavonic literacy. They are composed on beresty, thin pieces of birch bark that possess most of the virtues of wood-pulp paper, while requiring nothing for their manufacture. What is written on the beresty are, generally but not always, gramoty, texts or letters, usually in the Novgorodian dialect of Old Slavonic, but also, occasionally, in Karelian, German, or scattered other regional languages. A project of the Russian nonprofit organization Rukopisnye Pamiatniki Drevneï Rusi (Manuscript Monuments of Old Rus'), entitled Drevnerusskie Berestianye Gramoty (Old-Russian Birch Bark Gramoty), has catalogued and made available online a great number of medieval gramoty, searchable by year, by place of origin, by archeological dig, by condition of preservation, and by genre. There are around 956 catalogued gramoty from the period between 1050 and 1500 ad. Only eleven of these have been identified as having a literary or folkloric content, while most of the rest describe commercial transactions or legal disputes, or consist of transcriptions of biblical passages. It does not take much to earn the designation of literature. One Novgorod fragment classified as literary, No. 837, composed sometime in the mid-12th century and including a partial drawing of a bird, says simply: ОУАМЫШЬЛИШ[Ь]ЛИЖЄ Which gives us, when we add spaces between words: ОУ А МЫ ШЬЛИ Ш[Ь]ЛИ ЖЄ Which is to say, in modern Russian (dropping the initial word fragment): "А мы шли да шли," that is, "And we went and went," or, "And we went on and on," or, "We just kept on going." If No. 837 is the Odyssey of the birch bark gramoty, No. 521 is the Kama Sutra and the Song of Songs, a truly beautiful fragmentary poem, composed in Novgorod in the early 15th century. It is catalogued as a "love spell," and when properly spaced, it translates roughly as: "May your heart burn and your body and soul burn [with desire] for me and for my body and for my face." We are not drawn to these texts for their rich, living detail, any more than we are impressed with Neolithic stone tools in view of their horsepower. Their rough and fragmentary quality is their virtue and their poetry. This is what Anne Carson, most notably, understood in her faithful rendering of the fragments of Sappho, and it is what the human past has to most compellingly recommend it: its initial rudimentary form and subsequent further corruption. Alongside the hundreds of transaction records and complaints of theft or wrongdoing, we also find a handful of works produced by a boy by the name of Onfim—the Slavonic version of the Greek name Anthimos, borrowed, like literacy itself, from the Byzantine world. Some of Onfim's beresty are not gramoty at all and are not included in the database, since they contain no writings, but only drawings. Others are evidently homework exercises for which the boy has written out the Slavonic alphabet, or has composed basic words or rote sentences. Others still are a combination of words and drawings. Onfim produced the entire body of his work around 1260 in Novgorod. There are twelve surviving gramoty (Nos. 199–210), six of which are adorned with illustrations (Nos. 199, 200, 202, 203, 206, and 210). Three of the works feature Onfim's name (Nos. 199, 200, 203), either standing alone as a signature or figuring in a sentence. No. 205 has an incomplete drawing and an incomplete signature. It is the combination of the illustration and the name that lend a handful of Onfim's surviving works what looks to us, today, like artistic genius: the power of the name added to the rough vision of the world, reproduced in scratchings on bark. Onfim's human figures are stereotyped and instantly recognizable. Their faces feature two dots, and, often, a sort of capital I, a vertical line with long bars at the top and the bottom, which together form a single eyebrow, a long nose, and a purse-lipped mouth. (They make me think of Alice the Goon of Popeye fame, who, in turn, has long made me think of Vladimir Putin.) Human hands are represented as what look like pitchforks, with anywhere from three to eight fingers sticking up as straight lines directly out of a perpendicular base line. There are generally no bodies, but only legs that go straight up to the base of the head. Or perhaps there are only torsos that do not terminate in a groin, but just keep going, somehow, until they become feet. Onfim's favorite themes are men, horses, weapons, and mythical beasts. Gramota No. 200 has all the signature elements of a work by Onfim: the alphabet exercises, the horse, the weapon, the defeated enemy, and, finally, the signature. In the upper right corner, we have the beginning of the Cyrillic alphabet: А Б В Г Д Є Ж Immediately below these traces of rote exercise, the artist has written an inflected form of his name: ОНѲИМЄ Onfim is, we may presume, the rider on horseback, slaying the man on the ground like St. George slaying the dragon. His signature is at once the mark of handwriting practice, of proud authorship of a work of art, and, finally, a projection of himself into a fantasy scene. Though this work may be his most representative, it is not his most compelling. No. 206 gives us the most impressive assembly of pitchfork-handed men, underneath a text in which the author seems to have started out copying a passage of scripture (with a contracted Jesus: as in Byzantine Greek, all the charged and powerful words are shortened, as if by a sort of orthographic taboo), but to have shifted after just a few words to a syllabary exercise. Gramota No. 203, in turn, depicts a remarkable fantasy scene, and represents a perfect fusion of image and text. With the words properly spaced, we obtain: ГИ ПОМОЗИ РАБУ СВОЄМУ ОНѲИМУ Which is to say: "Lord, help your servant Onfim!" What exactly is happening in this scene? According to the Soviet philologist Artemii Vladimirovich Artsikhovskii, the words at the top of the gramota are a conventional and very common phrase in the period. He describes the figure at the left as a boy, and implicitly as Onfim himself, while characterizing the figure on the right as indeterminate, as perhaps a man with his hands raised, or even a tree. Most importantly, he determines that the figure on the right is incomplete, evidently abandoned as the artist lost interest. But it may be that Artsikhovskii's presumption of the "schematic" character of the figures, and the conventional character of the text, prevented him from giving the dramatis personae more than a casual glance. If we study them attentively, we will notice what appears to be a third person lying on the ground, with his legs sticking up in the air and three toes sticking out from the one visible foot. There is a man or a creature on top of the man on the ground, with wild hair waving on his head. He may be clutching a snake or venomous asp, or he may have the serpent wrapped in his hair, and he may have just killed the man on the ground by means of it. Though it may not be clear what Onfim intended, it is at least clear he has not abandoned this drawing for lack of interest, and, in this light, however conventional the phrase at the top of the gramota may be, when he adds his name to it, as the servant of the Lord to be helped, and places it together with the violent scene born not of convention but of his imagination, the phrase becomes anything but rote. The artist is imploring the Lord to help him in particular, Onfim, the subject and hero of this oeuvre. But we still do not know which figure represents him. If he is the boy on the left, then why should the Lord help this calm and passive onlooker? We might be tempted to imagine a comic-book succession of images, where the left figure is the first panel, and the boy who was initially passive is drawn into the action on the right. Such spatial representation of temporal succession has been identified in art as early as the parietal drawings of the Paleolithic period. There is no reason to suppose it must have been absent in medieval Novgorod. But if Onfim is in the "panel" on the right, is he the victim on the ground, or is he the monstrous assailant? Does he want the Lord to save him from attack, or to give him even more beastly power? Here we might look to gramota No. 199 for interpretive assistance. In this image, we know who Onfim is because he tells us. Speaking in the first person, the quadruped with the flayed tongue announces: Ѧ ЗВѢРЬ Which is to say: "I am a beast." In the text inside the box next to the beast, we find a dedication: "Greetings from Onfim to Daniel." There appears to be another figure, a human figure, on the ground in front of the beast. But it is not Onfim. Perhaps it is Daniel, Onfim's sidekick, being put in his place yet again, we might imagine, in the hierarchical order of their boyhood amity. Looking back to gramota No. 203 (they are not numbered in chronological order), it is hard not to see Onfim as the beast, subduing the man on the ground, so full of pride in his own power that he imagines the Lord himself will help him. * The standard line in the scholarship has been to trivialize Onfim's achievement. Artsikhovskii's preferred adjective is "infantile" (ребяческий), while in English-language commentary, authors have often drawn facile comparisons with "refrigerator doodles." Onfim is said to have been bored, to have been letting off steam, and to provide an illustration of the timeless truth that "boys will be boys." In its corrupted and fragmentary forms, what the past gives us is strange and powerful. Attempts to assimilate Onfim to the present, the everyday, and the familiar serve, consciously or unconsciously, to remove this strangeness. The Epic of Gilgamesh, too, is the work of schoolboys doing rote exercises, scattered writings that were statistically collated and made to seem as though they came from a single author. We praise the epic, whose author has been elevated by posterity to the rank of genius, for taking on the most difficult and enduring themes of literature: life and death, love, fallenness. The fact that they endure from ancient Mesopotamia to the present day does not license us to assimilate them, but rather opens up the possibility of perceiving depth, antiquity, and perennity in what we can ordinarily only grasp as our trivial and fleeting everyday life. It is not that the loves and losses of the ancients are merely like our trivial frustrations in online dating, but that these very trivial frustrations are inscribed within the long golden chain of human experience, and it is only art and literature that can reveal the length of that chain to us. It is not that ancient images of dragons and battle are merely like our refrigerator doodles, but that our doodles, or our children's, inscribe us into the life of the imagination, whose recording in material traces it is the business of art and literature to continue. It is easy to judge that Onfim's body of work is noGilgamesh, but here one might reply that what makes it less is also what makes it much more, namely, that it is the work of one person, and cannot be understood except in relation to that person: Onfim. Gilgamesh is no less anonymous than the Paleolithic stone tools produced millennia before it. Onfim's work is not only autographic; it is the autograph itself that is the subject of the work. The signing of the name is the insertion of the artist as the subject of the work. This self-insertion is remarkable particularly in the context of the Slavonic middle ages. As scholars such as Alain Besançon have shown, the Eastern Orthodox artistic tradition only appears to lag behind the supposed advances made in the visual arts in the Western European Renaissance so long as we fail to take into account the deep difference of its spiritual ends. The Orthodox icon in particular does a "worse" job of representing the world, in the sense of duplicating what we perceive in our visual field, than does Italian perspectival painting, but only because it is not the purpose of the icon to represent the content of our visual field at all, but rather to schematically—to return to a word Artsikhovskii had found suitable for his interpretation of Onfim—epitomize various tenets of religious dogma. Icons are not primitive or rudimentary attempts to duplicate the physical world; they are nuanced and complex attempts to embody the spiritual world. But if this feature of Orthodox religious art seems to invite a comparison to Onfim and to other supposed primitives, there is another sense in which our boy artist has decidedly nothing to do with the icon painters. In the Eastern spiritual tradition, icons are painted for God, not for the artist, though of course in practice reputations were made by great work and ruined by poor work. As in the case of the eponymous Andrei Rublev and his envious adversary Kirill in the great 1966 film by Andrei Tarkovsky, we may be sure that men in medieval Russia, as everywhere else, were driven by a desire for acclaim. Yet the ideal was one of selflessness, and the practice of signing one's name to a work never came into question. This only became widespread, in fact, with the rise of artworks as commercial objects in the burgeoning capitalist era of the late Renaissance in Western Europe: just one of many emerging techniques in 16th-century Florence and Flanders for keeping record of what belongs to whom. And yet, like Rembrandt, like Picasso, like George W. Bush, but like no icon painter in the vast surrounding territories in the surrounding centuries, like no Akkadian cuneiform copyist or Paleolithic flint-knapper, Onfim signed his name. This touch is modern, but is also rooted in the ancestral practices of writing that straddle the boundary between documentation and magical ritual, incantation, or spell. Gramota No. 521, as we have seen, by an anonymous author, sought to cause some love object's heart to burn with desire through the simple act of writing this wish upon a beresta. Writing, on a certain lost understanding, had the power to change the world, even if it was never subsequently read by human eyes, like the prayers inserted in the Wailing Wall, or the Sanskrit inscriptions written into the tops of Southeast Asian temples, to be seen only from the sky. It is difficult, now, to know whether Onfim's autograph belongs to the world of incantatory ritual, as in the writing out of love spells, or to that of proprietary documentation, as in the signing of a canvas whose loss one might otherwise risk in failing to record its provenance. Either way it is a powerful thing to write one's name: Onfim. He was a beast. Lord help him. __________________________________ From the Summer 2017 issue of Cabinet Magazine. Gramota No. 200.

Gramota No. 200.  Gramota No. 206.

Gramota No. 206.  Gramota No. 203.

Gramota No. 203.  Gramota No. 199.

Gramota No. 199.

Source: https://lithub.com/onfim-wuz-here-on-the-unlikely-art-of-a-medieval-russian-boy/

0 Response to "Medieval Servant Boy Line Drawing"

Publicar un comentario